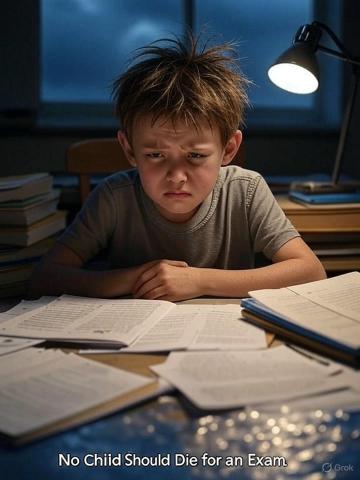

No Child should Die for an Exam

Sacrificing children has been a part of some societies in primitive cultures across the globe. By law, this was criminalised and declared a primitive practice in most parts of the world. However, little did we know how quietly these primitive practices have seeped into modern institutions.

Disconnected it may seem in the beginning, but I am writing about the board results. At a time when we celebrate board results, there are hundreds of families across the country who mourn the loss of their children’s lives. I wonder why we even lose a single child for the sake of board exams—an exam that holds no real significance, except for the intersubjective reality we attach to it

Excerpts from my chapter “The Impact Assessment” from my PhD thesis.

The importance of boards is delusional. It is like a lizard on the ceiling believing that it holds the ceiling from falling. In reality, it’s the pillars that hold the ceiling from falling, and for any normal person, the lizard is nothing but the pest intruder in the room. The pillars that hold our education system are our teachers, principals, children, parents, and curriculum. Remove one of them, and the teaching-learning will get crippled. Remove the board, teaching-learning will still continue.

In one of my earlier pieces titled “Agentic AI: Rethinking Identity, Consciousness, and the Role of Teachers,” I wrote how teachers play an extremely important role in creating the intersubjective reality. They shape the ‘who’ aspects of the children. They shape identity, and even AI cannot take this role. I am referring to it here to highlight that teaching-learning is an intimate act between teacher and children. Any meaningful things that we remember in our life that we learn are the outcome of the intimate relation or the deep connection we developed with our teachers, and learning is the obvious outcome of this deep connect. In the name of objectivity, boards take away the rights of teachers to assess children. When teaching-learning is a subjective issue, how can assessment be objective? In my earlier article titled Twice the Exams, Twice the Stress: The Flawed Logic of Biannual Board Exams, I have discussed how the introduction of CUET has totally made boards irrelevant.

I return to the question: what can we do if we are sensitive? If the lives of children matter to us. There could be some immediate and some long-term measures.

As an immediate measure, we must ban media coverage of board results. This creates unnecessary pressure. Children continue to appear in exams in schools and colleges—we don’t see media reports that this percent of students have been promoted from first to second year. It’s like a routine exercise, and this is how it should be. Media coverage makes it sensational and can be seen as the most direct reason that compels some children to take unfortunate steps.

The second step could be to adopt the learning corridor approach to assessment, not a thin line. Rohit Dhankar, in his article titled Beyond the Oxymoronic Idea of No-detention Policy, has elaborated on this idea, and I have also further discussed it in my blog article, Reimagining Schools: Moving Beyond Grades and Exams.

At present, we have a percentage system which differentiates between two children even with a one percent difference. This can be seen as if we have a hundred thin lines, and we place children on each of these lines in our assessment. The corridor approach could be that we have a wide corridor to place children together. Like in some Western countries, they practice the 4-point grading system. In this system, results can be classified into four quarters: children who scored below 25 percent are placed in grade 1, those between 25 to 50 in grade 2, children between 50 to 75 in grade 3, and those between 75 to 100 in grade 4. This will significantly reduce stress levels. Children are not stressed because they scored less—many of them feel the stress because they missed touching 90 percent and scored 88. All these issues can be addressed through this corridor approach of assessment.

In the long run, we must dare to imagine an education system free from the colonial scaffolding of school boards. These institutions were never designed to serve the child—they were meant to serve a system that needed fewer qualified individuals. In a modern, independent, democratic India, we must ask: whom do our boards serve today? Certainly not the children who are silenced under the weight of expectations, or the teachers whose professional autonomy is eroded.

If we truly value the lives and well-being of our children, then the question is not whether the board should change—it is whether we can afford to keep it at all. The Department of School Education can regulate schools. Institutions like NCERT and SCERT can shape curriculum and pedagogy. What we need now is not another reform of the board, but the courage to retire it.

Because no certificate is worth a child's life. No number on a mark sheet should be allowed to decide their worth—or take away their tomorrow.

If you wish to read more, I have explored these ideas in depth in a 10,000-word chapter from my PhD thesis, available here:

file:///C:/Users/HP/Downloads/10_chapter%207.pdf

- Log in to post comments